After two days of riding twisty dirt roads up and down hills, I was more than ready to enjoy the final descent down to the border crossing at La Balsa. I kept on the brakes to moderate my speed on the steep bits and carefully picked my line between potholes and corrugations in the road, until I came in sight of the unexpectedly picturesque river crossing that was the border checkpoint.

In that moment of inattention I managed to ram my front wheel squarely into a deep rut, which bucked me up and down and caused one of my rear panniers to detach and skid clumsily to a halt behind me. You never get a second chance to make a first impression!

I popped into the office on the Ecuadorian side, and, after half an hour of waiting, filled out an exit ticket, and received a stamp in my passport. I was free to go. I walked over the bridge to the Peruvian side of the river and poked my head into the immigration office, which turned out to be empty. One of the nearby guards broke off from chatting with his mates, stubbed out his cigarette, and wandered over to take a seat behind the desk. He asked me how much time I needed. I pointed at the bike and told him that I would like as much as he could reasonably give me.

‘Mmhmm’

Stamp.

‘You have 180 days. Enjoy your stay.’

‘That’ll do nicely. Thanks very much!’

From the border it was only 6 immaculately paved kilometers to Namballe. I wonder if the Peruvians had deliberately made sure that there would be an obvious contrast in the quality of the road surface on their side of the crossing.

Peru and Ecuador have long been rivals: Peru launched several wars of aggression against Ecuador in the 20th century, going after the mineral rich Amazonian territories. Each time that the belligerents ultimately reached peace talks, Ecuador always ended up ceding a bit more of its territory. Surely, this doesn’t exactly deter Peru from giving it another try down the road?

So yes, there is a bit of history between the two countries. Football matches are a very serious business, and, crucially, they both came up with their own version of the same seafood dish, Ceviche. When I left Quito many of my Ecuadorian friends entreatied me to go and try the Ceviche on the other side, in order that I might give my impartial verdict. From that moment onwards I found myself carrying the burden of a decision that would bring national pride to one, and disgrace upon the other.

While there were some Cervicherias in Namballe, I couldn’t get any of the ATM’s to work with my card, so I confined myself to the basic, more affordable dish of fritura.

I opted to take two nights off at a hostel before riding any further.

Without getting into too much anatomical detail, I seemed to have come very close to ripping myself a new orifice over the last few days of hard riding for the border. A spell of resting to allow open wounds to heal a bit was very welcome, so I spent a day writing up my latest blog article. PA12: Out of the Amazon and down to Peru.

The next day I made the 2000m climb over the hills to San Ignacio.

I got myself checked into a hostel, took a shower, washed my bike clothes, and hung them up to dry after a fashion. I couldn’t put it off anymore, it was dinner time, and there was a brightly lit Ceviche restaurant within a stone’s throw. It had all come down to this moment. I ordered a beer to calm my nerves, and waited for the chef to prepare the dish.

After a few minutes it was placed before me. I did the mandatory 21st century ritual of taking several photos of the offering, before getting to enjoy it.

This one is better.

Without a doubt.

I’m so sorry Ecuador.

Please don’t lynch me when I come back.

I’m going to shift back to talking about bicycles and related dramas for the remainder of this entry, but if you are interested in continuing further down the culinary rabbit hole, I recommend that you read 4 reasons that you must come to Ecuador, where I delve into a lot more detail on the delicacies that you can enjoy in that country.

Well, I had some very good reasons for wanting to divert my attention away from the bike at this moment, because in the space of 4 days I had managed to break two more of my derailleur hangers.

The first one went on the Ecuadorian side, while climbing up to Zumba. I wasn’t even pedalling at the time, but my chain somehow contrived to get itself jammed between the cassette and the spokes on the rear wheel. I got my hand in there to pull it out, which tugged on the derailleur in the process, bending the hanger. I tried to bend it back, but the bloody thing snapped on me.

3 days later I was rolling into San Ignacio. Upon getting a good view of the city I paused to take a photo.

After getting the shot, I plonked myself back on the bike and my right leg swung backwards as I pushed off from the curb, tapping the derailleur. I immediately heard the dreaded sound of something metallic bouncing off the spokes of the rear wheel, announcing another bent hanger. A string of foul language erupted into the afternoon sun.

I had set off from Quito with 4 spares. You would think that would have been more than adequate? Well by now I had been on the road for just a bit over a month, and I had already broken 3.

These components are designed to break relatively easily in order to reduce the chance of an impact causing damage to an expensive derailleur.

I’ve been messing around with bikes for years, often dragging mountain bikes unsympathetically through snaggy undergrowth, in and out of trains, planes, and the backs of cars. In all of this use and abuse I have never once broken a hanger, except on this bike.

Upon inspection of one of the broken examples I could see that the thing had been made out of some kind of low quality pot metal. It was incredibly brittle. Frustratingly, these hangers often have a shape that is specific to a certain make and model of bicycle. In my case, replacements were only available from the original manufacturer of my bike in the UK.

I had just put in an order for the last two that existed in the SJS cycles online store that very morning, but now it was hard to feel particularly optimistic about that number.

I got extremely close to putting the bike up for sale that night, I was just completely fed up.

I wrote a long email to Thorn Cycles about my situation, and my frustration with the manufacturing quality of their hangers, and then turned in.

I woke up after a restless night, to an inbox blowing up with emails. Robin, the director of Thorn, had copied me into all of the internal communication related to my order, and so I had a vantage point in witnessing their whole team search all over the shop for any additional hangers that might be lying around, and eventually managing to discover 2 more in the workshop.

That gave me 4 in total. Perhaps now I might stand a fighting chance?

They got the order out of the door and into the hands of a courier that very same day.

My Thorn Nomad Mk3 was designed to be equipped with a Rohloff internal gear hub. When they were building the bike, Thorn specifically recommended that I should go with a Rohloff for the sort of riding that I planned on doing, but, being the cheapskate that I am, I instead opted for the derailleur-equipped version for two thirds of the price.

I cannot fault their response to my crisis; Robin even added the two additional hangers free of charge. These people clearly really care about keeping their riders out on the road. I needed to stop moping around, pick myself up, brush myself off and make some kilometers disappear behind me.

First, I faced a long sweeping descent down into a valley. The road was in the process of being resurfaced with loose gravel all the way. I didn’t want to end up skidding off and knocking my teeth out, so I kept the speed down.

After a while I popped out at the bottom and found myself on a rather pleasant ride alongside a river, heading downstream.

Happy days, a nice gentle cruise for a while!

After a few hours the terrain really opened up.

Rice fields? Auto rickshaws? Am I in South East Asia?

This was without doubt the most idyllic section of riding that I’d done on this trip to date.

The afternoon sun gave a magical golden colour to the fields. I let my consciousness wander off and dissolve into my surroundings, the pedals seemed to spin around without effort, and the world washed over me.

At Puerto Tamborapa I shook myself out of my daydream to pick up a few supplies for a quiet night of camping by the side of the road, and then carried on riding. As the sun settled down below the hills, I discovered a patch of rough ground covered in weeds, where I made myself at home for the night.

The next day was steady climbing towards Jaén.

About an hour from the city a man beckoned me over, telling me that he had advice for my journey.

Milton turned out to be a Warmshowers host, and immediately recommended a more interesting road for me to take on my way out of Jaén. He told me to go and visit a ‘casa de ciclista’ in the city when I arrived.

I needed to get a Peruvian SIM card for my phone, message potential Warmshowers hosts down the road, and try to find someone who would be willing to be a recipient of my package of bike parts from the UK. I also reckoned that a haircut wouldn’t be a bad idea either.

I knew that it was going to take some time for the spare derailleur hangers to make it out to me, and if I somehow broke all of those as well I would find myself right back in the same position again. Thorn had told me that they weren’t expecting any new ones in stock for a couple of months at least.

You can never be 100% sure that a package will even arrive, and I’ve heard of cyclists being forced to pay hundreds of dollars in import duties for basic things like a new set of tires.

Therefore, as a contingency, I wanted to see whether I could also get some kind of substitute fabricated locally. It was probably overkill, but I was determined to put a stop to all of my troubles related to this tiny piece of metal once and for all.

But when should I take the time to do this? Presumably it would require a few days stuck in place, waiting for the job to be done.

While on my way out from Jaén I decided to drop in at the casa de ciclista, ‘El Ciclista’, that Milton had recommended to me the day before.

I casually mentioned my mechanical dramas to Miguel, the owner, who immediately responded that he knew several different people in town who ought to be able to make me a new, much stronger hanger, from scratch.

Miguel called various people over the course of the day, and even zipped off on his motorcycle to knock on a few doors, before finally getting a hit from a guy called ‘Cusco’. Cusco showed up in the evening and took my last spare hanger away with him, to fabricate a sturdier copy from steel. Fingers crossed!

It turned out that there was a cross country mountain bike race in San Ignacio on Sunday, and therefore everyone was coming in to Miguel’s shop to get their bikes serviced in advance of the competition. Miguel was on his hind legs all day, rushing between different riders with his tools. I’m really impressed by his generosity in finding time to help me, considering that this was probably his busiest day all week.

It seems like ‘El Ciclista’ also functions as the meeting hub for a whole community of cyclists from the city and surrounding area, all kinds of people came by just to hang out and natter for an hour or so.

Peruvians seem pretty relaxed about breaking the ice with a stranger. After getting stared down, and often receiving rather blunt responses when trying to spark up conversations with bystanders in Ecuador, it was a welcome change to have people calling out ‘gringo!’ or ‘amigo!’ to me in the street, and then having a friendly back and forth by the roadside.

One thing that might seem rather banal to remark upon is that, in Jaén, men mostly head out on the town wearing flip flops or sandals.

Now, Mexico and Ecuador are hot countries, and I would naturally prefer to be wearing shorts and open toed shoes to counteract this.

However, unless you happen to be on a beach, it seems to be very much frowned upon. I’ve had old blokes muttering that I’m being disrespectful, I often get a whole show of getting pointedly looked up and down, with a widening of the eyes. I would notice bystanders pointing and laughing, or muttering about how it must be a cultural difference.

Ladies seem to get a pass in this, and there seems to be nothing wrong with having your toes showing if you identify in that way.

So, you can imagine my relief in Jaén when I could finally kick off my sweaty bike shoes and let some air flow freely over my toes, and just… relax.

Miguel and his two mechanics, Luis and Carlos, gave my bike a thorough going over. They did a particularly great job on the brakes, putting on new, smoother, cable outers, disassembling and greasing up all the moving parts of the brake assemblies.

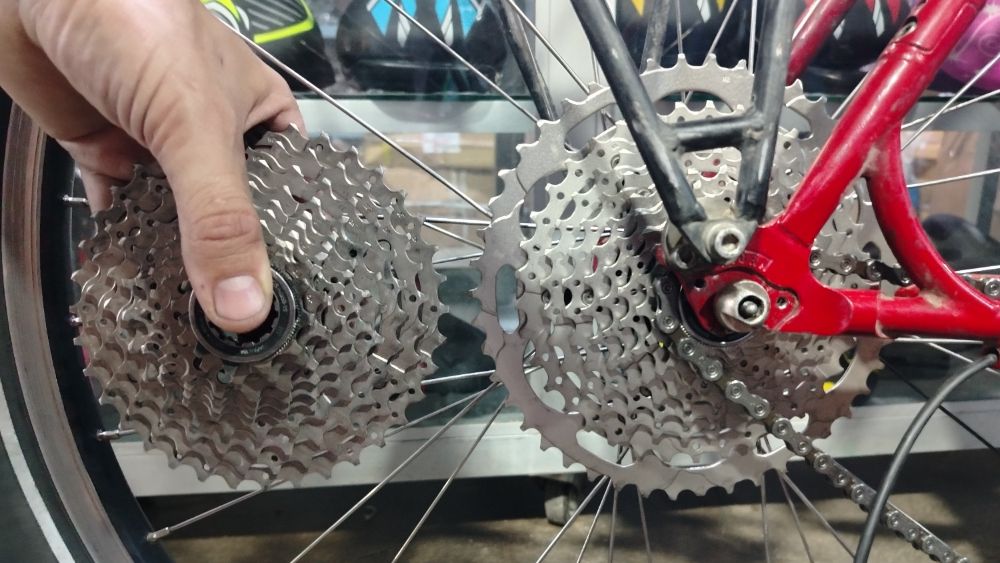

Miguel asked me why I hadn’t changed from my current 3 x 10 drivetrain, to a more modern 2 x 10.

By getting rid of the largest chainring on the front, I could put a significantly wider cassette on the back, which would give me a much lower gearing on the lowest gears.

Of course I would wind up losing a few of my higher gears, but I very rarely find myself using those, except to amuse my legs while the bike is already rolling itself down a hill at a good lick.

Besides the expense of the conversion, I couldn’t really find any reason not to go ahead with it, especially considering the huge terrain that I would be facing on the road ahead.

One week, and 1000 soles later (about £200), I rolled out of El Ciclista on a thoroughly serviced bike, with a completely new drive chain, and, crucially, a rear derailleur that was now attached by a bespoke, oil quench hardened, steel replacement of the original hanger.

I took a deep breath, made a quiet prayer that nothing was going to go catastrophically wrong with the bike, and gingerly made my way out of Jaén. Next stop, Chachapoyas?